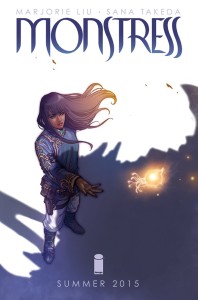

One of my faves, Marjorie (M.) Liu, recently gave an interview on her upcoming comic book, Monstress. Having only just started reading comics in the last year, I’m more familiar with her work as a novelist – particularly the Hunter Kiss series featuring bad ass Maxine who’s covered in living demon tattoos. Maxine is…complicated. But I love her for that very reason. I expect that much of that will be present in Monstress as well.

After reading this interview between Zachary Clemente of Comics Beat and Liu, I was left with a sense of how deliberate some of her choices were in writing this story.

…how come when we read quest-fiction — fantasy, science fiction – even when we watch movies or television with ensemble casts – we typically see, like, five men and one woman – or some other completely skewed number? On a practical level I thought it would be interesting, whether or not readers pick up on it, to shift the paradigm and have five women for every one man in my book, just to play with that and have it out there.

Notice how she makes a conscious decision to do this, to play with the level of visible women in her story. I tend to agree with her that fantasy is generally very boy- or man-centric. Just think of some of our favorite ensemble casts – The Lord of the Rings and the Avengers come immediately to mind. Usually there’s a token woman whose both super smart and super beautiful who may or may not be able to kick ass. But she’s generally alone in a sea of men.

While I don’t generally operate under the binary notion that reversing the status quo is helpful, in this case I think it is. Imagine how that sort of imagery works even subconsciously to encourage us to visualize more women in certain kinds of roles and spaces. Literature, whatever its form, has the power to make us do that.

These and other cultural products have has much ability to reinforce narratives as they do to disrupt them. When people from marginalized communities say that representation matters, we do so because we are faced on a daily basis with imagery and language that works in support of a system of power predicated upon whiteness and/or maleness. Five men to every one woman works to support this myth of men being naturally given to power or access or [insert “masculine” thing here]. A single “strong,” “powerful” woman in a sea of men is thereby an exception to the norm. She’s there because she beat out all the other less powerful, weak women. She’s there because she’s exceptional and, therefore, note like other women. All other women just need to be more like her so that they, too, can have her kind of access.

But five women to every one man? Those five women are there because they belong there, because they fit.

That’s the importance of this imagery, of this deliberate imagery. Imagine a little girl, or even a grown woman, seeing something like that. Imagine the possibilities.

And, again, notice the conscious choice Liu makes to do that.

Liu later says:

…[People of color have] spent generations working to be treated as full human beings in a society that is always trying to dehumanize us. And part of being a full human being is imperfection – being allowed imperfections.

And later…

There’s no such thing as a perfect person – that’s okay. We have to learn and accept that a person can be simultaneously good and decent in some areas, and a total Diablo in others. The heroine, Maika, is not a nice person. But why would she be?

What’s tied up in that demand for perfection, really? Because we live in a society of binaries, the call from POC populations to be seen as more than villains in many cases flipped to become representations of POC who are only perfect. But perfection is not humanity. And that is really what we’re after. Not only the chance to be the hero, but the chance to be represented as what we are – human. And that doesn’t even begin to get into the expectation that POC represent these unattainable ideals in order to have basic access to human rights. It’s a demand that’s meant to keep us in our “place,” and whether we’re seen as horrible villains or unflawed heroes, each role is used to prevent us from having greater access to the rights and privileges afforded to straight, white, cis-gendered, able-bodied men.

Whether we are comfortable with it or not, these cultural representations work in tandem with the social and political spheres to create environments in which POC are only seen as either stereotype or super perfect human – neither of which is a full representation of who we are. It is never just TV, or just a book, or just a film. They are reflections of the worlds that their creators inhabit. If, for instance, a white writer can only conceive of a POC as a noble savage (I’m looking at you Far Cry 3) or a magical negro (I’m looking at you Penny Dreadful) whose only purpose is to fuel a white man’s or woman’s story – then we have problem. And we still have a problem if a writer gives us a POC protagonist that has no flaws, makes all the right decisions, says all the right things, and is just flat and boring as all hell.

These notions of imperfection are why I can love Empire‘s Cookie and How to Get Away With Murder‘s Annalise and Black-ish‘s Rainbow. One of these women is perhaps more palatable to those given to respectability politics, but the point is that what we get here is a range of identities. They are wildly different women and none of them are perfect. As Liu asks, why should they be? Not a single one among us is.

I can’t wait to get my hands on Monstress, out at your local comic book store on November 4.